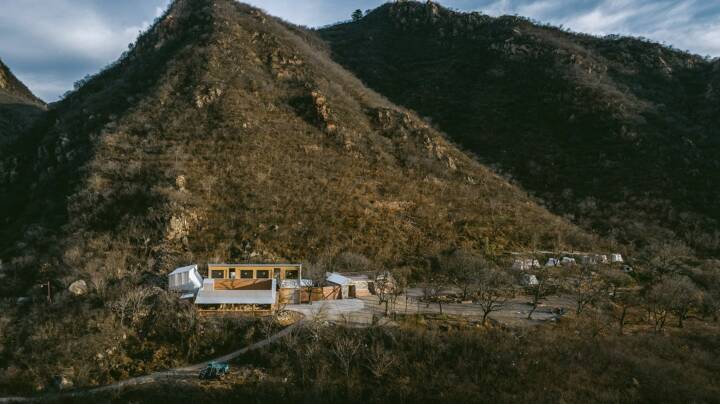

Architects: Wonder Architects Photography: Zhu Yumeng Construction Period: 2023 Location: Xishuiyu, China

In the early 15th century, the town of Huanghuazhen under Changping Prefecture was bustling with the construction of the Great Wall. Near the Xishuiyu area, in an unnamed valley, people carved out a terrace halfway up the mountain and hauled countless rough-hewn yellow stones there. It is speculated that a wall was intended to enclose the valley, but for some unknown reason, the project was abandoned, leaving the yellow stones scattered in a long mound.

In the land of Yan,

stretching over two thousand li,

with tens of thousands in armor.

Though the people do not depend on farming,

the fruits of jujube and chestnut suffice to feed them.”

——《战国策.燕策一》

From Strategies of the Warring States: The Strategies of Yan

Over the centuries, many chestnut trees were planted in this area. People lived and worked under the dense shade, and every autumn, the valleys within a hundred li were covered with fluffy chestnut husks.

In 2019, when we arrived, a construction team was stationed on the terrace. They had set up three or four makeshift sheds, with building materials and equipment strewn all over. Amidst the disorder, dozens of old chestnut trees still thrived. The largest required three people to encircle it.

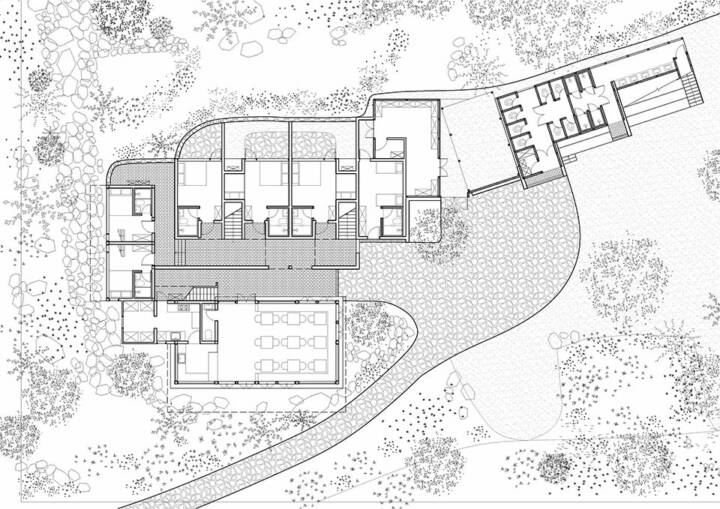

Read MoreCloseThe owner envisioned developing a campsite here, using terraced steps to set up several groups of tents.To serve the campsite, fixed facilities were needed on the platform. However, due to construction restrictions, the early randomly erected sheds had already defined the outline of the new buildings.

For architects eager to freely sketch blueprints, this was initially disheartening. Yet, upon closer examination of these sheds, it became clear that the workers were experts in mountain living. They knew where the foundation was stable, where more sunlight could be welcomed, and where one could hide from the howling mountain winds. Furthermore, they deeply valued the chestnut trees on the platform, skillfully weaving the sheds in and out of the trees.

Inspired by this, we reimagined the site.The sight of the ground covered in chestnut husks during autumn was particularly striking – a rare, abundant expression of the Yanshan region. Thus, we named the new structure “Full Chestnut Terrace.” In ancient China, “terrace” was a vaguely defined architectural concept. It could be a place for people to view scenery or a way for them to engage with it. We sought to re-establish the connection between people and the landscape amidst the remnants of the original sheds.

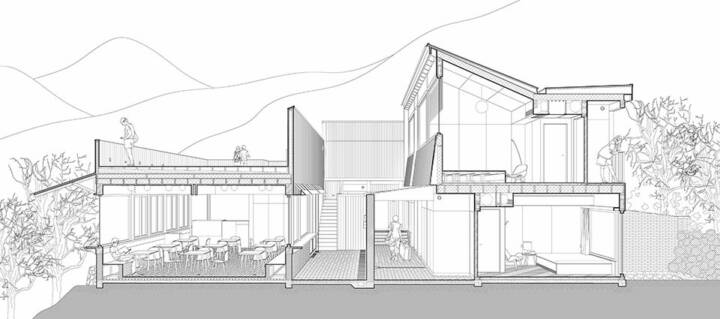

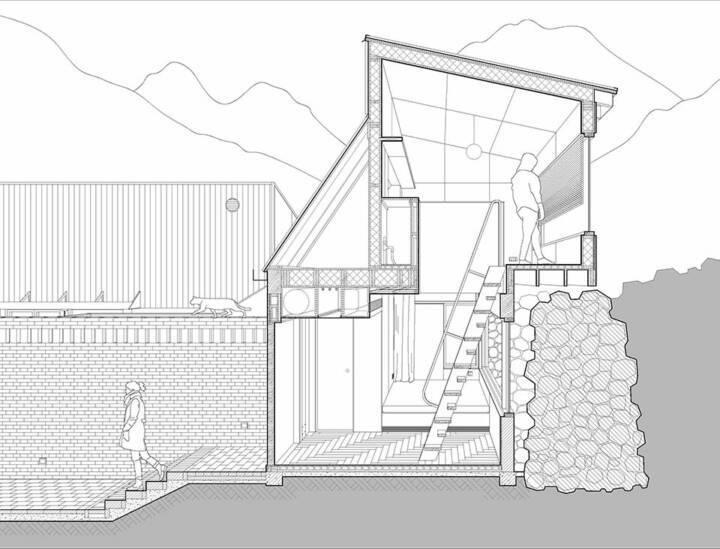

In some respects, the construction of these sheds was quite arbitrary. For instance, the roof was constructed to align with the prevailing direction of rain and snow, opting for the slope that allowed the most efficient drainage. As for the materials, a simple and practical approach was adopted. Leftovers of other projects were used to assemble the façade. However, these expedients resulted in an unexpected lightness and simplicity, forging a sense of freedom in this mountain architecture. There was much to learn here. Thus, we prefer to call the entire process a “reconstruction.”

The western side of the building, before and after the “reconstruction,” where the west wall is a remnant of the Ming Dynasty barrier wall, now detached from the original site

Due to the constraints posed by the mountainous terrain, the entire complex was built with wood, combining the use of timber frames and wooden shear walls within relatively compact building size.

In the timber-framed sections, we deliberately avoided traditional wooden structural forms. For example, the plan used an even number of bays, the façades were asymmetrical, and for the overhanging eaves, we abandoned wooden structures in favor of lighter and more authentic steel construction.

The wooden shear walls were designed to showcase the logic of “envelopment,” endowing the building with a corresponding sense of weight. The upper roofing was refashioned with corrugated metal sheets, reshaping the building’s exterior. The details echo the form language of the original sheds, making this envelopment more in line with the material’s constructional context. We envisaged “Full Chestnut Terrace” as a contemporary wooden structure, with modern technological features as its underlying theme.

When the site was still occupied by sheds, workers would pick up yellow stones from old piles to construct threshold walls and foundations for houses. During the reconstruction, we used old red bricks salvaged from nearby villages and towns to unify the disconnected building units at the ground level. Various slanted walls redressed the building’s outline, stretching between the plateau and the woods, creating a man-made layer distinct from the wooden houses. This bestowed a certain commemorative quality, forming a “relic” of this era.

Over a thousand years ago, the painter Fan Kuan contemplated the wintry mountains and rivers of the North and created “Snowy Cold Forest Landscape.” A millennium later, a similar scene emerged in a valley of the Yanshan Mountains. Rather than deliberate design, this owes more to the original shed builders who found the perfect composition for the architecture.

Artistic conception is a description of the imagination and a habit of viewing that condenses countless experiences. We hoped to bring new forms to the architecture while integrating it with the land in a familiar way. I am particularly fond of the Qing Dynasty painter Li Shizhuo’s “Viewing the Painting.” In the painting, scholars raise their cups, trying to drink with the figure in the painting. The artist arranged the two figures, originally on the same plane, along an upward sloping axis, creating a slight upward gaze. I find this an ingenious way to view scenery. In the spaces of Full Chestnut Terrace, we have embedded many such relationships.

In fact, before Li Shizhuo was born, the poet Nalan Xingde had already been observing the scenery around him. Interestingly, he likely visited the Huanghuacheng area around 1680, his duty being to herd horses for the imperial court. It’s conceivable that he visited the valley below Full Chestnut Terrace, and the chestnut forests on the hillside he saw were probably more lush than what we see today. It was in that year, on an early winter dawn, that he wrote the famous “Dian Jiang Chun · Early View from Huanghuacheng”:

In the wee hours after the first snow,

The snowfall levels with the guardrail in the dawning light.

How boundless is the western wind,

I rise and don my robe to behold the sight.

In this vast expanse,

Unwittingly, I let out a deep, prolonged sigh.

When will dawn come,

As the morning stars are about to fade,

Geese take flight over the expanse of white on high.

I too have waited for dawn atop Full Chestnut Terrace, yet never witnessed geese flying up from distant sandbanks. Sometimes I wonder, how would the twenty-six-year-old poet have reacted if, on that clear morning, he had chanced upon this house among the mountain paths…

Text provided by the architect.