Architects: KAUH Photography: Fernando Alda Construction Period: 2024 Location: Almería, Spain

THE PLACE IS EVERYTHING

La Hoya is a gorge located on the edge of the historic quarter, between the hills of the Alcazaba and San Cristóbal, and crossed by the Wall of Jayrán. During the High Middle Ages, it was occupied by a neighborhood that was later abandoned, turning into an agricultural space that over the centuries evolved until its decline, becoming a forgotten and expectant vacant lot.

Historic landscape restoration, environmental regeneration and spatial reimagination are intertwined to define this proposal which aims at the rediscovery and reinvention of this place. The act of revealing the story of this landscape in order to become part of the palimpsest of its evolution has been the main premise of this project.

The design was already there; in the hills that embrace this place, the wall that outlines its concave shape, the fortresses that guard it, the dike that contains it, the valley that widens it, the agricultural terraces that geometrize it and the network of channels that irrigates them, the archaeology that lays hidden below the surface, the escarpments and stone outcrops, the tones of its earth, its resilient vegetation, its wild fauna, its arid atmosphere and it broad blue sky. Our task was merely to tend to the features that we found, accentuating them by means of a soft intervention that is both minimal in its impact and highly specific.

Read MoreCloseThe actions carried out result from delving into the memory of this landscape in order to understand and maintain its configuration, explore its manifold scales, understand its unique form, identify its multiple environmental units, preserve and enhance its valuable ecosystem, shape its expressive materiality and atmosphere and find the construction techniques and material palette that make it all possible. All within the framework of discussion of what a park should be, both physically and symbolically, in the context of the current environmental crisis, in a heritage site such as this one, and in a climate like Almería’s. And with the goal of turning La Hoya into a space shared by agents, a habitat with no other added program than the mere enjoyment of such an exceptional place.

The park which has been imagined, the Mediterranean Gardens of La Hoya, is a landscape that comprises a monumental setting, an archeological reserve, a sanctuary for flora and fauna in the center of the city, a celebration of the semi-arid Mediterranean climate and a reflection of the culture of water of Almería.

DESCRIPTION OF THE PARK

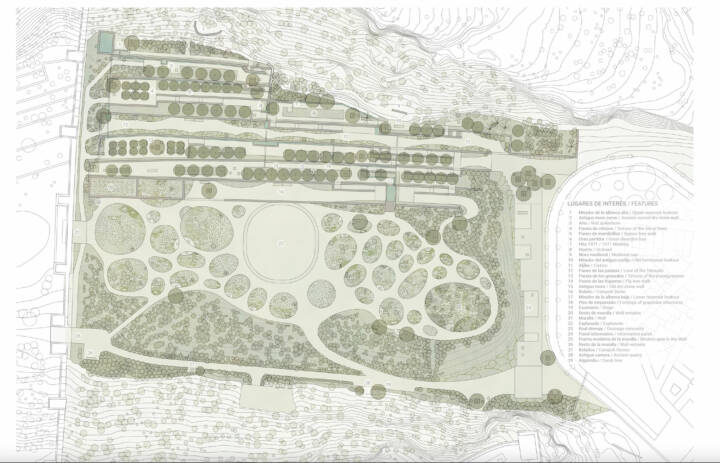

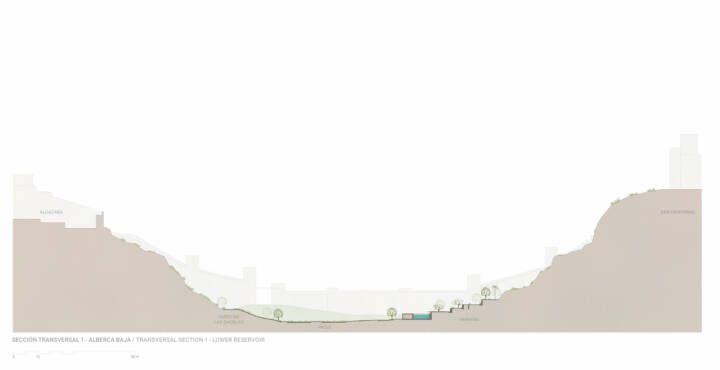

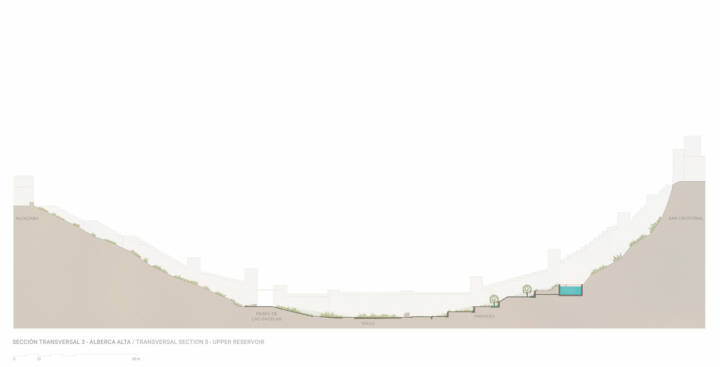

The park is bounded by the Hill of the Alcazaba to the southwest, the Hill of San Cristobal to the northeast, the Wall of Jayrán to the northwest and the Dike of Calle Luna to the southeast. From the city, this street gradually rises providing access to the park either at the foot of the Alcazaba or along the base of hill of San Cristóbal.

The top of the ancient dike, which is elevated with regards to the city, is tattooed with a combination of earthen and stone materials to become a balcony from which to look onto the entire space and have a panoramic view of the park, while contemplating the Wall of Jayrán. It also provides a perspective of the hills of the Alcazaba and San Cristóbal. The balcony topographically connects the bases of these hills and two of the structuring features of the site. On the one hand, it joins the preexisting lane that runs along the foot of the Alcazaba leading to the gate that gives access to the Research Center located beyond the Wall. On the other, it intersects with the intermediate level of the system of terraces contained by dry stone walls which sits at the foot of the hill of San Cristóbal

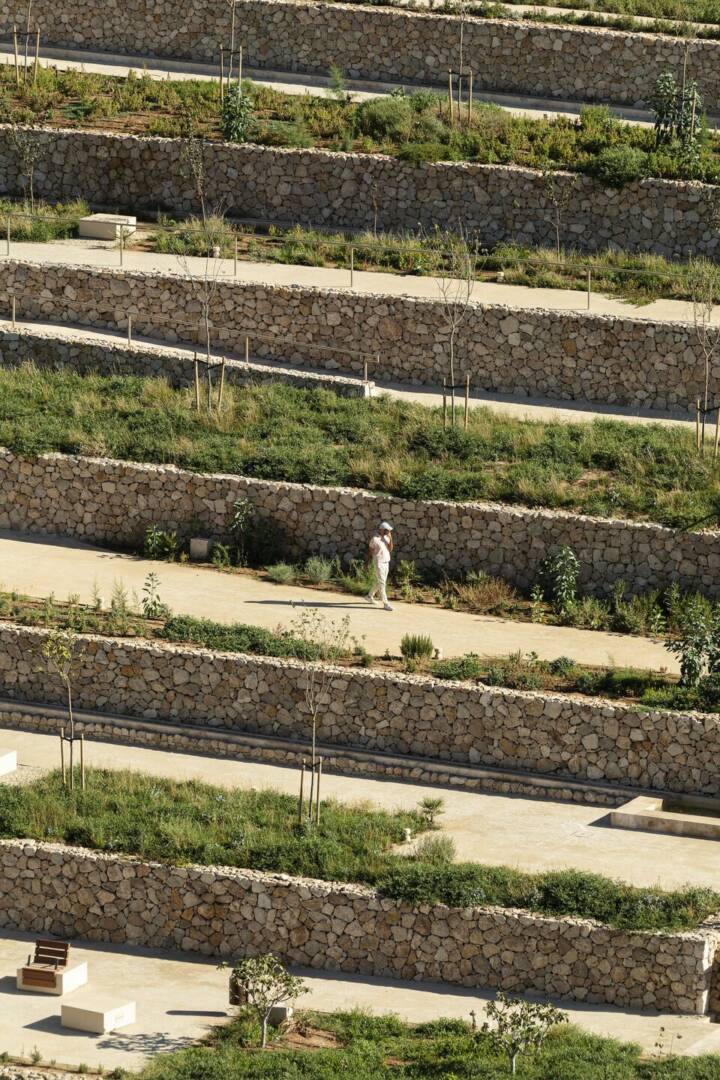

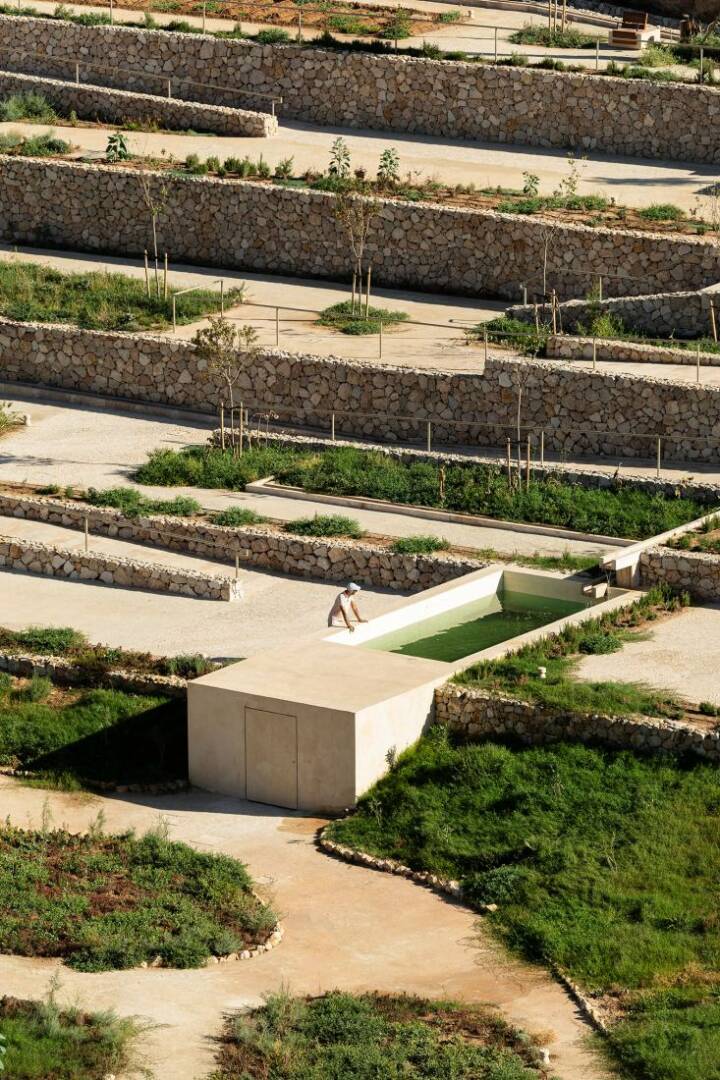

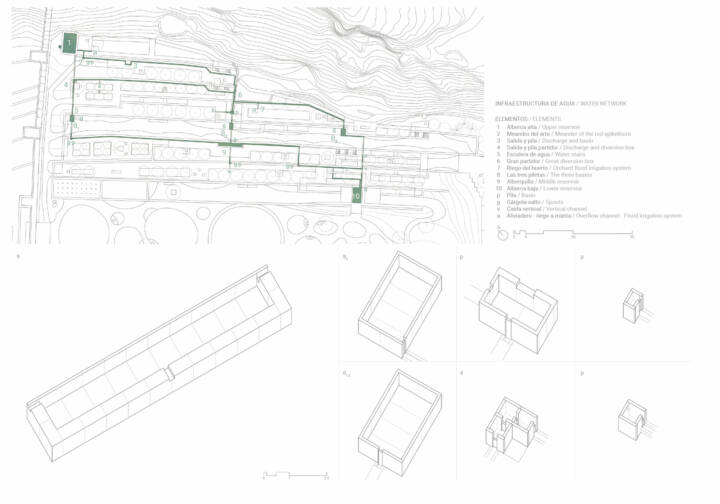

These terraces preexisted and have been maintained in their entirety, preserving their topographical levels and restoring their walls with additional stones originating, like all the natural materials employed in this project, from leftover stockpiles from nearby quarries. Stairs and ramps, also of a massive stone nature, have been implemented onto to these walls in order to define itineraries and provide access to the different levels. These itineraries are accompanied by a restored network of water channels that once provided irrigation to the different crops that were cultivated on the terraces. The two pools that served as reservoirs for this system have once again been put to use; the upper reservoir is the beginning of the system and the main water store, while the lower reservoir serves as the tank for the park’s current watering system. The project includes intermediate diversion boxes and basins that help regulate the flow of water, along with multiple features that provide sound, contributing to the atmosphere of the place.

Tree-lined paths and small resting spaces have been laid out along the terraces. The trees are of different species that speak of the agricultural past of La Hoya. The terraces enable the discovery of viewpoints over the park, new perspectives of the Alcazaba and the wall, and even provide glimpses of the sea over the rooftops of the city. They also allow the public to reach the base of the Wall. In the beds at the foot of the trees prairies of wild Mediterranean flowers have been planted in order to protect the soil and contribute to animal biodiversity—attracting insects and serving as a refuge for chameleons. The terrace that corresponds to the level where the former farmhouse once stood has become a vegetable and flower orchard, another terrace is dedicated to the cultivation of citrus trees, while the one that intersects with the balcony over the dike is conceived as an organic promenade recalling the time when spontaneous vegetation took over the space and blurred the linear order of the cultivated terraces.

This organic approach is the premise behind the preservation and restoration of the slopes that fall towards the valley from the bases of the hills and the dike. The paths that traverse them, which over the years had become well-established desire lines, have been maintained.

The valley of La Hoya, originally the dry river bed at the base of the gorge which later became the site where a medieval settlement once stood, is conceived as continuous plane and an archeological reserve with large groupings of vegetation—mainly native herbaceous plants and bushes— planted in a thick layer of added soil, traversed by multidirectional winding paths. These groupings are an abstraction of the forms that water leaves behind when it sporadically flows and where plants tend to group in these kinds of environments in arid climates, while in the park they also serve as infrastructural elements to manage its irrigation as well as the water from the occasional—and sometimes torrential—rains of this area.

In the center a large esplanade can be found, an open and empty space outlined by a ring of stone slabs where both spontaneous and organized collective activities can take place.

THE ELEMENTS OF THE PARK

La Hoya, known through time also as Oya, Oia and Joya due most likely to it geological formation, is part of the Alcazaba and Walls of the Hill of San Cristóbal heritage site of Almería. This complex is over one thousand years old, and it was declared a national monument in 1931. In La Hoya itself, at the foot of the Alcazaba, small quarries can be found excavated into the hill, with markings from the extraction of large blocks, probably used for the construction of parts the fortress itself or for other historical buildings of the city. These quarries are just an example of how, beyond the grand scale of La Hoya and its structural components there also exist a plethora of smaller material—and even immaterial—features that have also become part of the project.

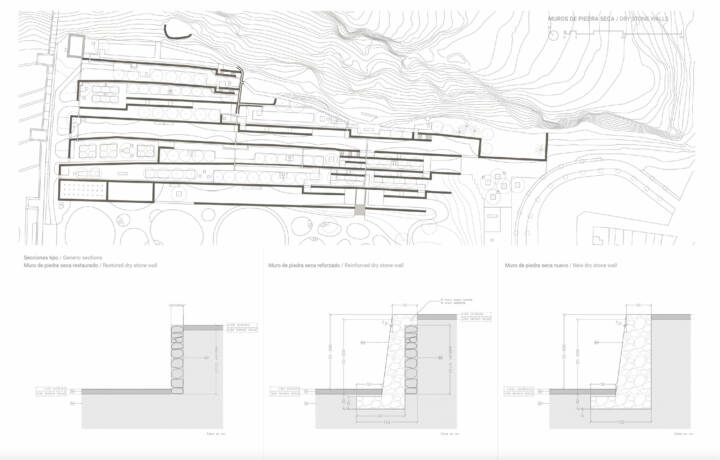

In Almería, the term “parata” is used for an agricultural terrace, and “balate” for the wall that retains it. The traditional dry-stone construction of these walls is a technique that has been declared Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO. The project has maintained the structure of terraces and walls of the farmstead that was established on the site in the 19th century.

Most of the walls were in a ruinous state, they were unstable and much of their material had been lost. This led to the decision to use what remained of these walls as backfill for new dry-stone walls, adding a minimal amount of lime-based mortar in order to provide them with the stability recquired given the new public use of the space. Sections of the original walls in a better state of conservation have been restored. In some of these sections, larger cantilevered stones jutting out of the wall can be seen; this was the traditional way of climbing between the different levels of the terraces. Catapult stones from medieval sieges of the Alcazaba can also be seen reused in the stonework of these walls. The catapult stones that have been found scattered throughout the site have been grouped together an placed next to the gate in the Wall of Jayran.

The Wall of Jayran is known as such after the first Taifa sovereign of Almería, who promoted its construction in the 11th century. It was built during a period of urban growth, and it was then when the neighborhood of Jandaq Bāb Mūsà was established in La Hoya. The Wall is made of rammed earth, it has a series of large towers and is doubtlessly the main feature of the site, not only due to its imposing presence, but also because it outlines the shape of the gorge. The gate that we see today was opened during a series of restoration works carried out by Francisco Prieto-Moreno in the 1950s, even though some sort of opening known as Bāb Mūsà must have once existed there during the Middle Ages. Next to the gate there are lose blocks of rammed earth that possibly come from the aforementioned restoration work. In fact, at the foot of the wall, in the center of La Hoya, another of these lose rammed earth blocks can be found, this one may have fallen from the wall during a flood in the 1950s. All of these remains have been integrated into planting areas of the park.

A similar course of action was taken with the many small concrete cubes that were found along the terraces during the first weeks of clearing the site. These rough elements shaped like truncated pyramids were used as footings for posts set at 2-by-2-meter intervals that held up the wiring to train grapevines, a structure that was the precursor of what became the Almería greenhouse. They have been gathered and laid out on one of the terraces.

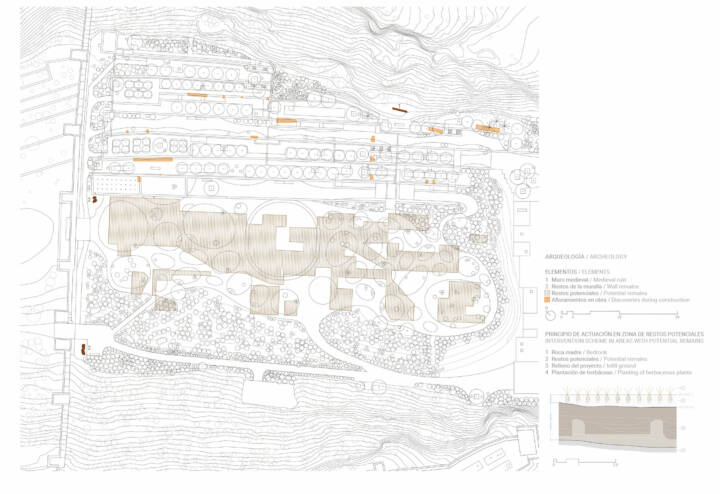

During the works, a large pile of rubble belonging to the farmhouse was removed. This three-story building, located on one of the mid-level terraces, had been abandoned and then demolished towards the end of the 20th century. As the area was being cleared away, the remains of rammed earth wall dating back to the Middle Ages was discovered, proving the existence of buildings from that period on the site. These remains had been used as foundations during later periods, either for buildings such as this one, or as backfill for the retaining walls of the terraces. That neighborhood was abandoned in the 13th century, and the space gradually ruralized. All the potential buried remains have become part of an archaeological reserve. The premise of the project has been preservation of these potential remains, and during construction measures were taken to avoid impacting those that were discovered. Among other precautions taken, the potential existence of remains, detected by a ground-penetrating radar, led to decisions regarding the exact location of trees or to the re-grading of the terrain of the valley by adding layers of soil in order to avoid excavating into the existing strata.

In the vicinity of the old farmhouse there is a well or a cistern excavated into the bedrock of the hill of San Cristóbal. This element was probably part of a rainwater catchment system before the water from the Channel of San Indalecio reached the area. This channel, built in the 19th century, was a large hydraulic infrastructure project built to provide irrigation to large swaths of land around the city. It began at the Andarax river and ended at “La Hoya behind the Alcazaba”. Nowadays it is no longer used but remains of it can be found scattered throughout the municipality. Among them, the feature where it ended: the upper reservoir of La Hoya. This pool made of stonemasonry walls has been restored to hold around 150 cubic meters of water. It was the beginning of the irrigation network that once watered the farmstead and now waters the park. The system is based on a series of channels that run along the base of each of the dry-stone walls in order to water each terrace using flood irrigation. The project has reconstructed this network, restored the large diversion box midway through the system and implemented new diversion boxes, basins, smaller reservoirs and vertical water features. Flood irrigation is still possible in a couple of instances. During the restoration of the system the markings ‘JCG 1971’ were discovered and maintained next to one of the channels; they were probably made by a worker who repaired the network that year. The network ends in the lower reservoir, the lowest hydraulic point of the terraces. Its structure has been reinforced and it now serves as the tank for the park’s drip irrigation system.

Almería’s desert climate has determined how such a precious asset as water is used. The climate here is characterized by its generalized aridness, long periods of drought and elevated sun exposure. The park adapts to these conditions, not only through its water management but also through the selection of plants. The plant palette comprises trees used traditionally in the agriculture of the area, along with native shrubs and herbaceous plants as well as cosmopolitan species also from the semi-arid Mediterranean spectrum. The most characteristic plant of the area is the red spikethorn (maytenus senegalensis), an endemic and protected species. All the existing specimens have been maintained and new ones have been planted, along with other native bushes to reinforce the presence of the species with which it coexists. The steep slopes are an example of this, since it was decided from the beginning to consider them non-accessible reserves. Therefore, all the vegetation participates in the environmental regeneration of the space.

After being used to cultivate grapes and fruit trees, La Hoya became a “prickly pear orchard”. Once abandoned, this crop took over and invaded the entire space. The cocheneil plague of 2015 killed most of the specimens, except for two which have been kept and integrated into the planting scheme. A collection of fruit trees has been planted on the terraces, including quince, jujube, pomegranate, mulberry, almond and citrus trees, along with other ornamental species that once existed near the farmhouse building, such as date palms and false pepper trees. Mulberry trees also dot the valley and the balcony. White-flowered Judas trees, chosen for their seasonal changes as well as for their formal and cultural significance, have been planted in rows along the terraces.

The park’s flora is accompanied by its fauna. Many animals live in La Hoya, among them chameleons, a protected species that has begun to flourish among the many new plants of the park and rocks of the walls. Sometimes Iberian wild goats can be spotted when they come down from the Sierra de Gádor following the steep slopes of the gorge of El Caballar, which La Hoya joins upstream. The presence of birds and pollinizing insects is also important and has grown since the intervention.

The Sierra de Gador is also where the quarries from which the stone for the walls comes from are located. The stones were found stockpiled as leftover and discarded material in an abandoned pit. The cut stone used for the pavement —cobbled areas and on ramps and stairs, as well as to manufacture the components of the irrigation network—channels, spouts, basins, etc.— comes from Sierra de Las Estancias, to the north of Almería.

The water-bound pavement, mixed with lime, has been chosen for its natural and chromatic characteristics and its drainage properties. The aggregate used—also a stockpiled as a residual material—comes from what are known locally as “Conan’s quarries”, just a couple of kilometers away from La Hoya. Coincidentally, and among other well-known movies, scenes from the 1982 film Conan the Barbarian were filmed in La Hoya.

These material and immaterial connections all constitute La Hoya, in the same way its human history and its natural processes have done and its current human and non-human inhabitants will. This contemporary landscape project simply gathers all of the them together.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE LANDSCAPE

Water, its presence and its absence, has shaped La Hoya. The geological processes that molded the Sierra of Gádor carved the gullies of the Caballar and La Hoya, leaving a hill in the middle of the alluvial plain facing the sea, upon which the Al-Qaṣba was founded to protect the caliphal city of Madīnat al-Mariyya.

During the period of the Taifa of Almería, the Wall of Jayrān was erected joining the hill of the Alcazaba and the hill known then as Layham or al-Mudayna, and the streambed was drained. Here, the neighborhood of Bāb Mūsa remained inhabited for over a hundred years. With the decline of the city, the enclave was abandoned, turning into a large vacant lot. In the centuries that followed, when it became known as “oya”, “hoya” or “joya”, it ruralized, the land was cultivated and used for cattle rearing.

At the end of the 19th century, the agriculture of Almería enjoyed a period of splendor, and the arrival of water to the site thanks to the Channel of San Indalecio transformed the space. At the foot of the hillside of San Cristóbal a farmhouse was built, the land around it was terraced using dry stone walls and two pools and a network of channels were laid out for irrigation. Fruit trees, grapes, vegetables and prickly pears were cultivated.

Over the course of the 20th century, the Alcazaba and the Wall became heritage sites. In the 1950s, when the Wall was repaired, the gate was opened and the lane that leads to it was created, which at the time continued and led back up to the Alcazaba surrounding the hill.

On the other side of the Wall, on the site of another former farmstead, an acclimatization institute was established, and when it began to accommodate gazelles, it became the refuge for Saharan fauna we know today.

Towards the end of the 20th century the agricultural use on this side of the Wall disappeared, the terraces were abandoned and the farmhouse was demolished. The prickly pears, which would later disappear due to a plague, took over and mixed with other native species, such as the spike thorn, thus providing shelter for many animals, some of which are protected, such as the chameleon.

This place became the forgotten backyard of the city, serving as an uncontrolled dump harboring irregular activities and as a vacant lot used, from time to time, as the setting for movies.

With the advent of the new millennium a competition was organized for the design of a park that would reclaim the place for public use and showcase the values of this location. The idea was to establish a green space to ensure the preservation of this heritage site and enhance the space. As a result of the winning entry, today the Park of the Mediterranean Gardens of La Hoya is a reality.

Text provided by the architect.